A US destroyer, named after five Irish-American brothers who died in the Second World War, visits Castletownbere in Cork in 2003 .

In Saving Private Ryan four brothers were lost in battle and a fifth, the youngest, was located behind enemy lines and hauled home.

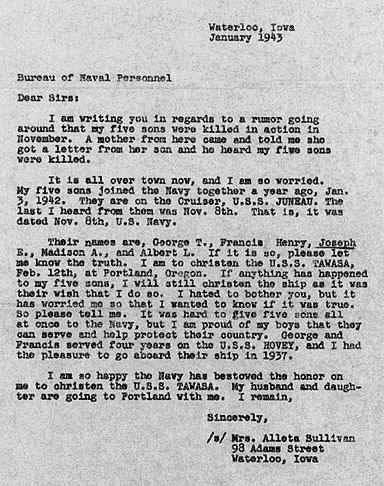

But real life is always harsher than the Hollywood version. When the USS Juneau was torpedoed by the Japanese in the South Pacific in 1942 all five of the Sullivan brothers lost their lives. And, even though one of them survived on the surface for three days, the rescue operation came too late to bring him home. There was no 'Saving Private Sullivan'.

The Sullivans

The Sullivans were a working-class Irish-American family of five boys and one girl from Waterloo, Iowa. They were descended from a young couple, Tom and Mary Bridget O'Sullivan, who left the Beara Peninsula, the very shadow of Hungry Hill, in 1849 at the height of the famine. Growing up, the five boys - George, Frank, Eugene, Matt and Al - were notorious rascals who graduated into a rough and ready band of brothers not to be messed with. Their father, Tom, a grandson of the Beara emigrants, was a quiet man.

Band of Brothers

In his book We Band of Brothers: The Sullivans and World War ll, John Satterfield tells the story of how, as children, the boys found an old boat on the river bank, plugged its leaky holes with mud and set off for their first adventure on the water. As the boat began sinking in the middle of the river four of them swam to safety, leaving toddler Al clinging to what remained of the wreck until nearby adults came to his rescue. Grandma Abel, a great believer in the value of family, was outraged by the abandonment of Al and the punishment was harsh. In future, they learned, they were to stick together no matter what.

"We Stick Together"

Initially the older boys, George and Frank, left Iowa to join the navy in San Diego and did a four-year tour of duty before returning home, full of great adventures and stories of the ocean. Meanwhile the three younger ones had come of age. Eugene was working in a local service station and riding a Harley Davidson and Matt was breaking hearts in the dance halls. Young Al had married a girl named Katherine in February, 1941, when they were both just 17, and now had a baby son, James.

In December, 1941, the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbour. And, as the five Sullivans were listening to radio reports with growing anger, they decided to join the navy together. Al should not even have gone - the navy was not recruiting married fathers. The recruitment officer had a problem on his hands. If he didn't accept Al, the other four would not join up. And it was also a deal breaker if he didn't have them assigned to the same ship. The Sullivans got their way. Not even Katherine would hold Al back. Her permission had to be granted for his enlistment and she gave it. "She knew how it was with the Sullivan boys," their mother Alleta said afterwards. "They did everything together."

Despite repeated pleas from their navy superiors to separate, the boys took up assignments to the USS Juneau in February 1942. There were eight pairs of brothers among the ship's crew but five from one family was definitely unusual. They initially operated in the Atlantic and then headed out for the South Pacific where the US Marines had invaded Guadalcanal and were holding the islands at the southern end of the Solomon chain against Japanese attack.

On Friday, November 13, 1942, a Japanese torpedo hit the Juneau and destroyed her in seconds. Young Al Sullivan was in the loading room of turret five and, according to author John Satterfield, he wouldn't have had a chance. Frank, Matt and Eugene were elsewhere on the ship and probably died instantly.

Witnesses from other ships in the fleet spoke of the enormous sound of the blast, the dark cloud of oil and smoke which engulfed the area and the incredible weight of debris which came flying through the air. The commanders of the other ships took the view that all 700 crewmen on board had been killed and they directed their own ships towards safer waters. The lives of any survivors were weighed against the safety of the other ships and deemed secondary. They were wrong. It is estimated that 140 men were still alive in the water after the Juneau sank.

George Sullivan, who had been on the fantail of the ship, was thrown clear by the blast. He made it to a life raft with other survivors, burned, injured and covered in oil. The ultimate survivors recall that he was screaming the names of his brothers. He grabbed toilet rolls, blown from a store room to the surface, and swam through the bodies wiping oil from the faces, desperately trying to find the features most familiar to him. All around him men were moaning and dying from their wounds.

In a tragic bungling of communication the ships making their way south assumed that news of the sinking would be relayed by a B-17 which was in the area and a rescue mission would be launched. The flight crew did not realise the onus on them and, according to Satterfield, they merely filed a standard report when they returned to their base.

Three days were wasted while the survivors, many without shirts on their backs, burned under the South Pacific sun. They held on to whatever boards, flotationrings or rafts they could find. They had no water and when the night fell they shivered in the chilling waters.

Their numbers dwindled. George Sullivan stopped calling his brothers and accepted the terrible fact that they were gone. Delirium set in and a far more sinister danger approached. As the oil cleared, the blood and human flesh in the water drew sharks and a number of sailors were killed.

Allen Heyn, one who made it back alive, saw George Sullivan reach the end of his tether. Delirious, wracked by grief and without hope of rescue, George took off his clothes one night and said he was going for a bath. "He . . . got away from the raft a little way and the white of his body must have flashed and showed up more because a shark came and grabbed him and that was the end of him," recalls Heyn.

In the end only 13 men were picked up. In the aftermath heads rolled for the miscommunications, purple crosses were awarded posthumously, a movie was made of the Sullivans and a battleship was named in their honour. But nothing would compensate the family for the loss of the boys. Only Al's baby, James, could offer some comfort in the quiet empty house in Waterloo, Iowa. After the first battleship was decommissioned a second one, a guided missile destroyer, was launched under the name The Sullivans, officially using the brothers' motto: "We Stick Together".

This weekend she sails into Berehaven, the harbour of Castletownbere, to commemorate them. Ships from the Irish and French navies will accompany the American ship on her visit. Tomorrow morning a flotilla will sail up towards the village of Adrigole. John Sullivan and his sister, Kelly Sullivan-Loughren - Albert's grandchildren - will lay a wreath at the old homestead from which the young emigrant couple, Tom and Mary Bridget O'Sullivan, left for America, never dreaming that their as yet unborn family would draw such honour back to the Beara peninsula.

Who were these heroes?

* George Sullivan: George was the eldest and leader of the pack. He was a light-hearted rogue who was often in trouble. He was the last to die, some three days after the Juneau sank.

* Frank Sullivan: A more serious character than his older brother, Frank was a keen boxer and a good seaman. He was promoted in the Navy.

* Eugene Joseph Sullivan: The middle son, Eugene (sometimes known as Joe), brought his Irish heritage in his genes and was nicknamed 'Red' because of his red hair and freckles. Motorbiking was his passion.

* Madison 'Matt' Sullivan: Matt was the quietest of the five and the most like his father. He loved music, was sought after by girls as a great dance partner and left a fiancee after him.

* Albert Sullivan: A lovable charmer, Al, the youngest, was 17-years-old when he married Katherine and 18-years-old when their baby, James, was born. He died at the age of 20.