Castles

The Siege of Dunboy

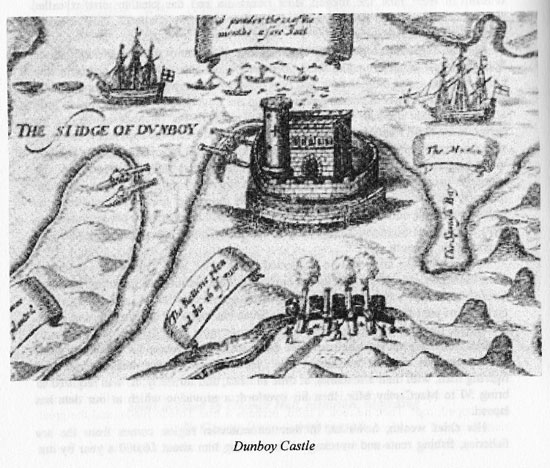

After the battle of Kinsale, the Irish Chieftains held a council of war, whereat it was decided that O'Neill should go to Ulster to defend the Northern province, O'Donnell to Spain, and O'Sullivan was to guard the interests of the South. On the nth of January, 1602, Don Juan not only capitulated for the garrisons of Baltimore and Castlehaven, but also for Dunboy castle on the Beara peninsula.

Captain Roger Harvey and Captain Flower had been commissioned on the 10th of January to take possession of those fortresses. Harvey was successful in taking possession of Baltimore and Castlehaven, but Flower failed to reach Dunboy by reason of foul weather and contrary winds. He lost fifty of the soldiers he had on board and all his crew, except seven, from some infection.

O'Sullivan hastened to Dunboy and arrived safely, but he was refused admittance to his own castle. In the night, however, he mined his way into a weak spot of the castle which he well knew, bringing with him 84 men, among whom were the Jesuit, James Archer; Thomas Fitz-Maurice, Lord of Lixnaw; Donnell MacCarthy, Richard Tyrell, Captain William Burke, and Dominic Collins, a friar. A thousand brave soldiers were within gun-shot outside.

At the dawn of day, Archer knocked at the door of Savadra, the officer in command, and requests his presence in " O'Sullivan's Chambers." He comes, and is informed that the Irish are in possession of the castle, that they would guard it for King Philip, that there was no use in resistance since they had a thousand men abroad within musket shot, whom they could call to their assistance if needed. Savadra was bewildered, and a few of his men discharged a shot or two, killing three Irishmen. The Spaniards were then disarmed, and sent to Baltimore, but some gunners, by request, remained behind; there was no compulsion in their regard

Don Juan de Aquilla, on hearing of the surprise of the castle, became enraged, and took it as an affront, and felt his honour compromised. He thought he was in honour bound to go back and retake the castle, and give it into the hands of her majesty. Mountjoy and Carew suggested that it was not his fault that the castle was surprised, that he need not trouble about it, for "they were desirous to see his heels towards Ireland."

Donnell O'Sullivan Beare, writing to King Philip on February

20th, 1602, says:—"I came to their presence, tendering my obeysance to

them, in the name of your majesty, and being with four hundred at my own

cost, towards your service I yielded out of my mere love and good will

without compulsion or composition, into their hands, in the name of your

majesty, not only my castle and haven, called Bearehaven, but also my

wife, my children, my country, lordships, and all my possessions, for

ever to be disposed of at your pleasure. " They received me in that manner, and promised (as from your highness)

to keep and save the said castle and haven during the service of your

grace. Notwithstanding, my gracious lord, conclusions of peace Was

assuredly agreed upon, betwixt Don Juan de Aquila and the English, a

fact pitiful, and (according to my judgment) against all right and human

conscience. Among other places, whereof your greatness was

dispossessed, in that manner which were neither yielded nor taken to the

end they should be delivered to the English, Don Juan tied himself to

deliver my castle and haven, the only key of my inheritance, whereupon

the living of many thousand persons doth rest, that live some twenty

leagues upon the sea coast, into the hands of my cruel cursed,

misbelieving enemies, a thing, I fear, in respect of the execrableness,

inhumanity, and ungratefulness of the fact, if it take effect, as it was

plotted, that will give cause to other men, not to trust any Spaniard

hereafter, with their bodies or goods upon those causes."

O'Sullivan placed a garrison in Dunboy under Richard McGeoghegan, and

placed three Spanish guns and sixty men on Dursey Island, where there

was a fort built by his uncle Dermot. He had about 2,000 followers

altogether under the command of Richard Tyrell.

He captured during the

winter his cousin's Castle of Cariganass.

On the 9th of March, 1602, Carew despatched the Earl of Thomond to

Bantry and Beare, and gave him some definite instructions. He was to

leave no means untried to get Donnell O'Sullivan Beare into his hands.

He was to give all the comfort he could to Owen O'Sullivan. " Have

special care," he says, " to prosecute and plague the O'Crowleys who

assisted Dermot Moyle MacCarthy. Sir Owen MacCarthy's sons, if they be

well handled, will prove the best instruments of doing so, as he stands

between them and the lord of the country."

Mountjoy, writing to the English Council, says:—

" As for Finan

O'Driscoll, O'Donovan, and the two sons of Sir Owen MacCarthy, they and

their fellows, since their coming in, are grown very odious to the

rebels in these parts, and are so well divided in factions amongst

themselves as they are fallen to preying and killing one another, which

we conceive will much avail to the quieting of these parts."

Thomond did his best to carry out the instructions, and marched as far

as Bantry, where he learned that the Irish under Tyrell and O'Sullivan

had occupied a strong position near Glengariff. The sons of Owen

O'Sullivan and O'Donovan were at the time assisting the Earl,who,

leaving a garrison of 700 men on Whiddy Island, thought it the wisest

course to return immediately to Cork.

Meanwhile, O'Sullivan was not idle. He cut off the Whiddy garrison from

all outside aid, and harrassed them so that they had to abandon the

island, and to set out for Cork. O'Sullivan, with his cousin Owen,

pursued the retreating army and captured their baggage, and would have

destroyed them had they not met Carew's army at the nick of time.

Carew, recovering from a severe illness, and still feeble and weak, and

acting contrary to the pressing advice of friends, who urged on him the

hopelessness of the enterprise, representing that Dunboy Castle was

impregnable, that there were no roads, no bridges, leading to it, that

the country was rough and rocky, with many narrow passes where a few

determined men could destroy a whole army, started from Cork on the 20th

of April, 1602, with 3,000 men. On the 30th the army arrived at

Dunamark, where stood a castle built some hundred years before by an

ancestor of Sir George. Here the army remained for a whole month

awaiting the arrival of the ships, which were to bring victuals,

munition, and ordnance.

In the meantime Carew sent for Sir Charles Wilmot, who was operating in Kerry with about 1,500 men, to join him—a movement which Tyrell and his men did their best to prevent, by occupying the passes south of Killarney. They kept him off for some time, but on the 12th of May he performed a remarkable feat, making a night march over Mangerton mountain, and then pushing on to Inchigeela. Carew joined hands with him at Cariganass on the 13th of May. Tyrell was forced to retire before superior force.

Letter to the gunners in DUnboy

On the 1st of May, Captain Taaffe made a foray with a troop of horse, and brought in 300 cows, a great number of sheep, and some horses. On the 3rd the sons of Owen O'Sullivan made a foray, and brought into the English camp 50 cows and many sheep. There was no compensation in such cases, and many innocent men were robbed of their property. We infer there was no poverty at the time, as there could not be where there were so many cattle. On the 7th of May Carew wrote the following letter to the gunners in Dunboy: —

" A letter from the Lord President to the Spanish Cannoniers in Dunboy.

" When Don Juan de Aquila (General for the Spanish Armie in Ireland)

departed from the Citie of Corke, having a care of your safeties,

requested mee to favour you, saying that contrary to your willes the

traytor Donnell O'Sullivan (by force) held you in his Castle of Dunboy,

there to serve him as cannoniers, I now calling to mind his desire (in

the love I beare him, being so great a captaine, and so honourable a

person as he is), and in consideration of the promise I made him, doe

write this letter unto you, promising (for the reasons before mentioned)

that when I shall sit downe (with my forces) before the castle (where

you are) if then you will quitt the same and come unto mee. I will by

the faith of a gentleman and a Christian, make good my promise to Don

Juan de Aquila, not onley to secure you in coming to mee, and in the

like safetie to bee with mee, but also to relieve and supply your wants,

and likewise at your pleasure, to accommodate you with a ship, and my

passport, safely to passe into Spaine, in such manner as hath been

already accomplished to the rest of the Spanyards that are returned to

their countrey.

" This above written I am obliged by my promise to Don Juan to fulfill.

But if you have a desire to finde or receive further favours at my

hands, you may with facilitie deserve it, that is, when you leave the

Castle to cloy the ordnance, or maybe their carriages, that when they

shall have need of them,they may prove uselesse, for the which I will

forthwith liberally recompense you answerable to the qualitie of your

merit.

" Lastly, if there bee in your companies any strangers (English and

Irish excepted), which are likewise by force held (as you are) these my

letters shall be sufficient to secure their repaire to me, and also to

depart, as hath beene before mentioned, condionally, that you and they

present yourselves unto mee, before our ordnance shall begin to batter

the Castle of Dunboy aforesaid. But if on your part default be made, I

holde myselfe clearely acquitted of my promise made to Don Juan, and to

be free from breach of faith on my part, and you ever after incapable of

this favour of my promised offer. Returne me your answer by this bearer

in writing, or by some other in whom you have more confidence."

" From the Campe neere Bantrie, the Seventh of May, 1602.

" To the Spaniards held by force in the Castle of Dunboy."

This letter, which is characteristic of Carew and his methods, produced

no effect on the Spanish cannoniers, which proves that they were not

detained by force. On the 31st of May the army left Carew Castle and marched towards

Bantry, and encamped that night a little further on on the Carbery

shore. A strong garrison was placed on Whiddy Island.

1st - 5th June

On the 1st of June the Earl of Thomond and Sir Charles Wilmot's

regiments were embarked for Beare Island; on the 2nd Sir Richard Percy's

regiment followed; and lastly the Lord President. There was some

difficulty in landing the pieces of battery on the island, but this was

effected eventually underneath the church, probably where the present

pier stands.

On the 5th of June, Thomond, with the knowledge and consent of the Lord

President, sought an interview with Macgeoghegan, the Constable of the

Castle, and this took place on the western end of the island. He thought

he might be able to corrupt the Constable by promises and bribes, but

in this he failed. Macgeoghegan, who belonged to a once powerful sept in

Westmeath, could not be corrupted. He advised Thomond not to hazard his

life by attempting to land on the main, for " I know," said he, " that

you must land on yonder Sandy bay, where before your coming the place

will be so intrenched and gabioned that you must run upon assured

death."

6th June

On the 6th, being Sunday, a wild and rough morning, the President very early rode out, accompanied by one attendant. He went two or three miles to the west of the island, where he got a view of the Sandy bay, Caematrunane, the place where the Irish thought he would land. He saw that it was well fortified. He then got a pinnace and went across to Dinish Island. This island is separated from Sandy bay by a narrow sound. He examined the place carefully, and found it would suit his purposes. The middle of the island was high ground, and so he could land his army on the east end of it, or on the mainland, without being seen by the enemy. He also found near at hand a natural platform, whereon he might plant his cannons to protect his forces while landing. The President and the Earl of Thomond's regiments were then embarked, and were landed at Dinish Island. They were formed into a battalion, and ordered to face the enemy as if he intended to attack them, and thus force a landing at Caematrunane.

7th June

Sir Richard Percy and Sir Charles Wilmot's regiments were likewise

embarked, but they were landed on the main land under shelter of the

island, and were landed before the Irish discovered the deception. The

two first regiments then crossed in boats, while the Irish ran from

Sandy bay to oppose them. They had to travel over a mile of rough

country without a road, and had to cross a rapid river without a bridge,

so when they came up all were landed. " Nevertheless," states the

Pacata Hibernia, " they came on bravely, but our falcons made them

halt." Twenty-eight of the Irish were slain and thirty wounded. There

were two prisoners taken and presently hanged. Seven of the English were

wounded. The army encamped that night about Castledermot, which was at

the eastern end of the present Castletown. No trace of the castle

remains, and the residence of Dr. Lyne occupies the place where it

stood.

On the 7th the army encamped within a mile of Dunboy. The President,

taking with him Sir Charles Wilmot and a guard of 100 men, went out to

reconnoitre the castle and surrounding ground. Contrary to the opinion

of all, he found good ground for encamping, about 240 yards west of the

castle, but out of sight of it by reason of high ground intervening. He

also found, not 140 yards distant from the castle, a natural platform

for planting his cannons. On the 8th two falcons were mounted near the

camp, which played on those working about the Castle, but they did not

hurt anyone, the range being too long.

There was some difficulty in transporting the ordnance. It was decided

to put the cannon into small boats which were to sail through a small

creek called Faha Dhuv, and the entrance to this creek was commanded by

the guns of the castle, but nearly a mile from it. Captain Slingsby

volunteered to perform the task if he was provided with thirty

musketeers. He placed those in the hold of the vessel, from which they

kept up constant firing. Many shots were fired from the castle at them,

but no one was hurt, probably because the guns failed to carry so far.

11th-12th June

On the 11th the English entrenched their camp and mounted their ordnance. On the 12th a contingent of 160 men, under Captain John Bostock, accompanied by Owen O'Sullivan and Lieutenant Downing, embarked in four boats for Dursey Island, and arrived there early the next morning. A landing was made on the north side of the island, where they found the walls of a ruined monastery constructed, Philip O'Sullivan says, by Bonaventura, a Spanish bishop, and long destroyed by pirates. A party of men under Lieutenant Downing were stationed there. Then the Captain got into a boat and rowed around the island, with the view of discovering a fit landing place. He decided to land the body of his men on the east of the island, and sent word to Lieutenant Downing that at the very instant the forces were landing he should deliver an attack on the north side of the fort held by the Irish. The fort was now attacked from three different points. The defence was stubborn at first, but after some time the outer work and three Spanish cannons were abandoned by the Irish. They fought in the inner fort for two hours, and then surrendered on condition that their lives were spared. They were all carried to the camp and executed. Five hundred

13th June

On the 13th Tyrell made a night attack on the English camp, but he was repulsed. On the 16th the trenches were finished, and three cannons were planted 140 yards from the castle. On the 17th, about five o'clock in the morning, the cannons, consisting of one demi-cannon, two whole culverins, and one demi-culverin, began to play on the castle. About nine o'clock in the forenoon a turret annexed to the castle on which an iron falcon was placed, and which kept up a constant fire on the English battery, tumbled down, many being killed by the falling masonry. The ordnance then played on the west front of the castle, which, by one o'clock, was forced down. Upon the fall thereof the Irish sent a messenger offering to surrender if their lives were spared, and allowed to depart with their arms. The President handed him over to the marshal, by whose orders he was presently executed. Carew would have saved the lives of many of his men if he had come to terms with the enemy, but the shedding of blood did not affect him.

Now the Lord President thought

everything ready for an assault, and he ordered his men to enter the

castle. At this moment the great carnage commenced. The English rushed

in through the breach.

The besieged poured on them shot and stones, and ran them through with

pikes and felled them with their swords, repelling gallantly the attack.

The English thereupon drew their artillery nearer to the castle and

made a greater breach. The Irish, who were only about 140 strong from

the first, had now lost many of their men, and, owing to the wreckage

that surrounded them, they were unable to use their arms with advantage,

so the English rushed through the breach and into the great hall, where

a bloody conflict ensued. The English lost many in this hall, and they

had to quit it, leaving behind many dead. The English now brought fresh

men to the attack, and the Irish were wearied, and wounded after long

fighting. After a sharp contest they entered the breach, and seven

companies carried their colours into the hall.

Many fell on both sides, and there were heaps of dead bodies in the

hall, on which ran streams of blood. Amongst the others, MacGeoghegan

fell, half dead, covered with many wounds—not one of the Irish remained

unwounded. At this stage some forty of the Irish made a sally out of the

castle to the seaside, but they were surrounded by the enemy and put to

death. Eight tried to save their lives by swimming, but Captain Harvey

and Thomas Stafford kept guard over the sea and shot them down. Those of

the Irish that were able, 77 in number, had now to betake themselves to

the cellars, where the fight was continued with great vigour. Dominick

Collins, formerly a cavalier in the French army, and now a Jesuit,

rendered himself up, and was some time after carried to Youghal, his

native town, in which he was executed. It was now sunset, and the

English army withdrew to their camp, leaving a strong guard over those

in the cellars.

On the 18th, in the morning, twenty-three yielded, with two Spaniards

and one Italian. Thomas Taylor, an Englishman's son, was appointed

commander and relieved Richard MacGeoghegan, who was mortally wounded.

The new commander drew into the vault of the castle nine barrels of

powder, and, with a lighted match in his hand, threatened to blow up all

near the castle if they did not obtain promise of life. He was

eventually prevailed upon by his companions to render himself

unconditionally. There were 48 more with him in the cellar, and when Sir

George Thornton, Captain Harvey and Captain Power came into the cellar

to receive their submission, Richard MacGeoghegan, perceiving that the

Irish were about to surrender, " raised himself from the ground, caught a

lighted candle, and staggered towards a barrel of powder," which he

would have ignited had not Captain Power taken him in his arms, and he

was instantly killed by some soldiers. Thus died the bravest of the

brave ! The Pacata Hibernia states:—"The whole number of the ward

consisted of 143 selected fighting men, being the best choice of all

their forces, of which not one man escaped, but they were either slain,

or executed, or buried in the ruins, and so obstinate and resolved a

defence had not been seen within this kingdom." Those men were chiefly

drawn from Westmeath and Connaught, and trained by Tyrell, a great

commander. The English lost about 600 men at the siege of Dunboy. Carew

had an army of 4,000 or 5,000 under his command, of whom scarcely 500

were English.

Carriganass Castle

Was probably built in 1540 by Dermot O'Sullivan, a member of the O'Sullivan Beare sept (or clan), who wielded considerable power in West Cork during the 16th century and early 17th century. The castle passed through the hands of various members of the O'Sullivan clan during a period of internal feuding lasting until 1601, when the O'Sullivans united to support Hugh O'Neill at the Battle of Kinsale. Following the English victory at Kinsale, one of the commanders, Sir George Carew, pursued the O'Sullivan forces back to their base on the Beara Peninsula. A small garrison was left at Carriganass while the bulk of the O'Sullivan force returned to Dunboy Castle; Carew's army easily captured Carriganass before continuing on to lay siege to Dunboy. The O'Sullivans were subsequently dispossessed, and the castle later passed into the ownership of the Barretts, who retained it until the 1930s. During their tenure, a new house was built next to the castle, which deteriorated into its present ruinous state.